Author: Madison Schroder

Most of the 2023 state legislative sessions have come to a close and it has been quite the year for nuclear energy. Since January, I have tracked more than 70 pieces of legislation across over 30 states that all have something to do with nuclear energy — from policies aiming to appropriate funds for a feasibility study to bills attempting to lift a moratorium so that it is actually legal to build it. I also had the opportunity to participate in hearings and provide verbal and written testimony for many of these bills. Here are 4 key takeaways about the state of nuclear energy policy in the US.

1. Republicans champion nuclear policy- but Democrat and bipartisan support makes all the difference

There is no doubt that one political party took charge of the nuclear movement this past spring. Behind approximately ⅔ of the tracked pieces of pro-nuclear legislation were solely Republican sponsors. This support did not stop at the introduction of these bills either. In both committees and on the floor, Republicans overwhelmingly voted to push these policies through on their own, with Democrats either voting against nuclear legislation or not voting at all (see Arkansas HB1142 and Indiana SB176). In fact, many of the successful pieces of pro-nuclear legislation across the country ended up being the result of an entirely Republican effort, with the Left taking little to no part.

This does not mean that nuclear did not receive any bipartisan or Democratic support this session. In fact, bipartisan support often made a significant difference when it came to successful legislation. For example, Colorado’s HB1247, which explored the use of advanced reactors in rural areas, and SJR79 in Kentucky, which establishes a Nuclear Energy Development Working Group, each had sponsors from both sides of the aisle and likely would not have passed into law without it.

While this might be common sense, that if both sides of the aisle agree on legislation then it is bound to be more successful, this collaboration sets a tone for nuclear legislation moving forward. The brute force approach in Republican-controlled states may be the most efficient way to make progress on nuclear, but these party-line votes reinforce the idea that nuclear energy is a partisan issue, something that has largely been overcome by Democrats at a federal level. Moreover, utilities, investors, and developers will have a lot more confidence to move forward with nuclear projects if the political support seems transpartisan and enduring.

2. States are obsessed with advanced nuclear (whatever that means)

Across several states, there appears to be widespread interest (about 20 bills worth) in exploring advanced nuclear technology, a deceptively amorphous term. To better understand what we mean when we talk about “advanced nuclear” or “advanced reactors”, I highly recommend this blog from Dr. Nick Touran. In it, Dr. Touran explains that “advanced nuclear reactor” is used loosely to refer to improved reactors compared to older designs. He notes two main definitions: reactors incorporating lessons learned into new optimized designs, like GE’s ABWR and Westinghouse’s AP1000; and reactors with extended capabilities beyond current light water reactors, like breeding fuel, higher efficiency, industrial heat, enhanced safety, and modular construction.

To give a glimpse of this wide-ranging legislation, Indiana’s SB176 which passed in April defines advanced nuclear as small modular reactors that have a generating capacity of no more than 470 megawatts and “is capable of being constructed and operated, either: alone; or in combination with one or more similar reactors if additional reactors are, or become, necessary at a single site”. Meanwhile, Maine’s LD1549 has a very similar definition of small modular reactors, except the generating capacity is limited to 350 megawatts. Then we have Minnesota’s HF3002, which manages to conflate the sodium-cooled fast reactor (which uses solid fuel) and molten salt reactors while excluding the Natrium reactor, which, at 345 megawatts, is larger than the stated definition of 300 megawatts or less.

It is also important to look at the policies states pursue once they have decided what they mean when it comes to advanced nuclear. A particularly interesting phenomenon comes from states attempting to lift bans on new nuclear construction in their state. AB65 in California and SB76 in Illinois were both first introduced as bills to lift existing moratoriums, but during the legislative process, both of these bills were amended to only lift the ban for “advanced nuclear.” California made this change to only include small modular reactors or those defined as reactors with an “electrical generating capacity of up to 300 megawatts per unit.”

In Illinois, the shift to advanced nuclear is far more broad, defined as a nuclear fission reactor with “significant improvements” compared to those operating before December 27, 2020, including enhanced safety features, reduced waste, improved fuel performance, and increased flexibility for integration with various applications and energy sources. This gels with the federal definition of advanced reactors, as stated in NEIMA, the Nuclear Energy Innovation and Modernization Act. Despite SB76 gaining overwhelming bipartisan support in the legislature, merely five days before the end of the 60-day window where it would have automatically become law without a signature, Governor J.B. Pritzker chose to veto the bill. Pritzker argued that this definition was far too broad, claiming that “the vague definitions in the bill, including the overly broad definition of advanced reactors, will open the door to a proliferation of large-scale nuclear reactors that are so costly to build that they will cause exorbitant ratepayer-funded bailouts”.

There are a couple of implications of this widespread interest with little coherence in concept. On one hand, states could end up writing narrow definitions that, if passed, would arbitrarily restrict promising advanced reactors based on size or coolant type. On the other, existing technologies such as the AP1000, which have proven to provide immense amounts of carbon-free, reliable electricity to millions of Americans could be eschewed in favor of a technology that is not yet operable. Either way, it is difficult to determine whether successful bills that cling to overly specific guidelines of what constitutes advanced nuclear are ones to be celebrated as a partial victory, or opposed by the pro-nuclear movement.

3. Workforces are struggling– and state governments know it

In a February 2023 blog post written by the CEO of the American Nuclear Society (ANS), Craig Piercy expressed concern that as the US interest in nuclear grows and climate pressures ramp up, sector heads were growing concerned by a lack of workers. Currently, over 100,000 Americans work in the nuclear sector, providing 20% of total US electricity and nearly half of the carbon-free power in 2022. This number will need to increase significantly as states pursue decarbonization objectives and transition away from fossil fuels.

However, the workforce is not growing at a pace to reach this demand. First, the number of graduates with nuclear engineering or related degrees has been relatively stable. Secondly, the rate at which skilled trade workers such as welders and electricians are retiring is surpassing the rate of those entering the workforce. While the cause of this gap is due to many factors, proper investment into encouraging young workers to pursue nuclear engineering and nuclear trade apprenticeships is lagging.

Prescient legislators across the US are recognizing this gap and trying to do something about it, but the progress is slow. Between January and June of 2023, 14 bills were introduced that would appropriate funds for nuclear workforce development. Of these 14 bills, two have passed- West Virginia’s HCR11 and Virginia’s SB1464. States such as Wyoming failed to pass nuclear workforce development legislation, despite being the site of the TerraPower Natrium project replacing a coal plant in the town of Kemmerer. Without proper investment into workforce development, for both trade workers and college-graduate engineers, states looking to expand nuclear energy in their state may have a hard time finding men and women to get the job done.

Many states are beginning to acknowledge that they need nuclear

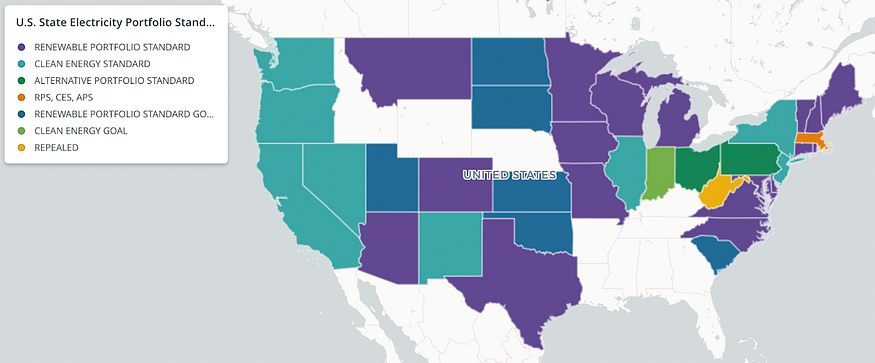

With heightened anxieties about climate change, many states in recent years have adopted clean energy portfolios with greenhouse gas emission targets and other related goals. What many of these initiatives have in common is that they focus narrowly on using technologies like wind and solar. Contrary to these commitments, several states in this session looked to expand their use of nuclear power to meet their energy needs.

Colorado passed their renewables-only climate plan through HB1261 in 2019, which states that “Colorado shall strive to increase renewable energy generation and eliminate statewide greenhouse gas pollution by the middle of the twenty-first century and have goals of achieving, at a minimum, a twenty-six-percent reduction in statewide greenhouse gas pollution by 2025, a fifty-percent reduction in statewide greenhouse gas pollution by 2030, and a ninety-percent reduction in statewide greenhouse gas pollution by 2050”. Despite this strict commitment to renewables, in May 2023, the Colorado state government passed and signed HB1247, which will appropriate funds to conduct studies assessing advanced energy solutions in rural Colorado, including advanced nuclear. Seeing this, it would not be surprising if Colorado adopted a more inclusive clean energy standard in the next few years.

States like Maine and Oregon, which both have comprehensive renewables-only climate plans, also pursued legislation to study the use of nuclear power in their state. Maine shut down their last nuclear reactor, Maine Yankee, in 1997 due to opposition from environmental groups. Since then, the state has adopted “Maine Won’t Wait”, an environmental plan including initiatives to reduce carbon emissions using renewable energy. In the 2023 session, several lawmakers in Maine co-sponsored LD689 and LD1549, a bill to study the construction of a new nuclear power plant in the state and another to seek informational bids for small modular reactors. Oregon, which closed its only reactor in 1993, has a nuclear moratorium and an entirely renewables-focused climate plan. Surprisingly, they also pursued, unsuccessfully, nuclear legislation in 2023. HB2215 aimed to lift the moratorium in the state, and SB832 would have removed this ban for just small modular reactors. Both of these bills make sense, considering that NuScale, one of the trailblazers for small modular reactors, was born and continues to develop its reactors in Oregon.

The recent developments in nuclear policy across various states signify a growing recognition of the need for a diversified energy portfolio to address climate change effectively. While many states have embraced renewables as a primary strategy, the inclusion of nuclear power in the legislative agenda demonstrates a willingness to explore all viable low-carbon options.

So now what?

Over the past seven months, state legislatures across the United States engaged in vigorous discussions about the future of energy for their constituents, with nuclear energy often taking center stage. A solution previously discussed with hesitancy and taboo, political allies of nuclear spoke proudly about its ability to cut carbon emissions, preserve land, support local economies, and bolster grid reliability. It is unclear what caused this shift, but a combination of extreme weather events, the high-profile grid failures in places that have invested heavily in intermittent sources, and the energy-independence-reality-check stemming from the war in Ukraine have made the nuclear story resonate more widely. Regardless, as states continue to seek solutions to their energy problems with nuclear, it is impossible to ignore the environment in which these bills are entering into. Is the United States ready to handle all of this new interest in nuclear power? Can our current regulatory frameworks keep up with demand? Will proponents be able to overcome lingering anti-nuclear sentiment? And finally, how quickly can we get more Democrats on board?

If you are interested in any of the bills listed in this article, please follow the links below (listed in order of mention):