Why developers should put community spaces at the heart of future nuclear power projects.

Author: David de Caires Watson

There’s talk of a nuclear rennaissance, of nuclear being the energy source of the future. Yet the industry remains shrouded in secrecy.

A van with tinted windows pulled to a stop in front of our minibus. The side door slid open and two menacing soldiers in military fatigues jumped out.

“Who was it that took the photos?” they demanded. Gulp. “Er, me?” I squeaked.

“You must delete the photos before you can leave. Photos are forbidden.”

This was how my trip to a nuclear plant ended — being forced, in front of soldiers, to delete photos of the outside of a civilian, electricity-generating station (I’ll save the plant and country the embarrassment of naming them). There’s talk of a nuclear renaissance, of nuclear being the energy source of the future, yet the industry remains shrouded in secrecy.

Secrecy, security, and public trust

A culture of extreme caution when it comes to security is damaging public trust in nuclear technology. Low public acceptance of nuclear can be a major barrier to achieving broad government and investor support. This could seriously derail the climate plans of countries where nuclear is being relied upon.

This secrecy can partly be traced back to the Cold War when East and West were in a technological arms race, and partly to international rules and norms that restrict information about plant layouts and other sensitive information.

Rightly, there are controls on detailed design information and the exporting of materials from civilian nuclear that could have a “dual-use”, i.e. be misappropriated for military purposes. However, this is a very small percentage of what makes up a nuclear plant, much of it being very similar to a gas or coal plant.

It is easy to be overzealous in the application of secrecy and security. Classifying everything may be simple, but it has unintended consequences for public trust. “What are they hiding?” you’re left wondering.

The terrorism threat

Back in the late 90s, my parents took us then kids to visit Wylfa nuclear power station in Anglesey, Wales. I distinctly remember being taken on a physical tour of the plant. I was fascinated by the walk-in radiation scanner and its disembodied voice. The visit was definitely an important step on my journey to a career in nuclear.

That tour shows that by the 1990s the industry was learning to open up, that not everything needed to be secret. However, the 9/11 attacks added terrorism to the list of security threats, leading the UK to end public plant tours and to introduce armed police to nuclear sites. It was decided that controlling security was more important than engaging with the public in this way.

Even if visits today are mostly limited to mockups in a visitor center, they do remain an invaluable way to teach both young and old about what goes on inside these anonymous concrete buildings.

However, the sites themselves are generally unwelcoming industrial places, surrounded by high-security fences and patrolled by armed guards. One’s nerves are a little on edge throughout, and there’s a palpable feeling of relief as you drive away.

Waste not, want not

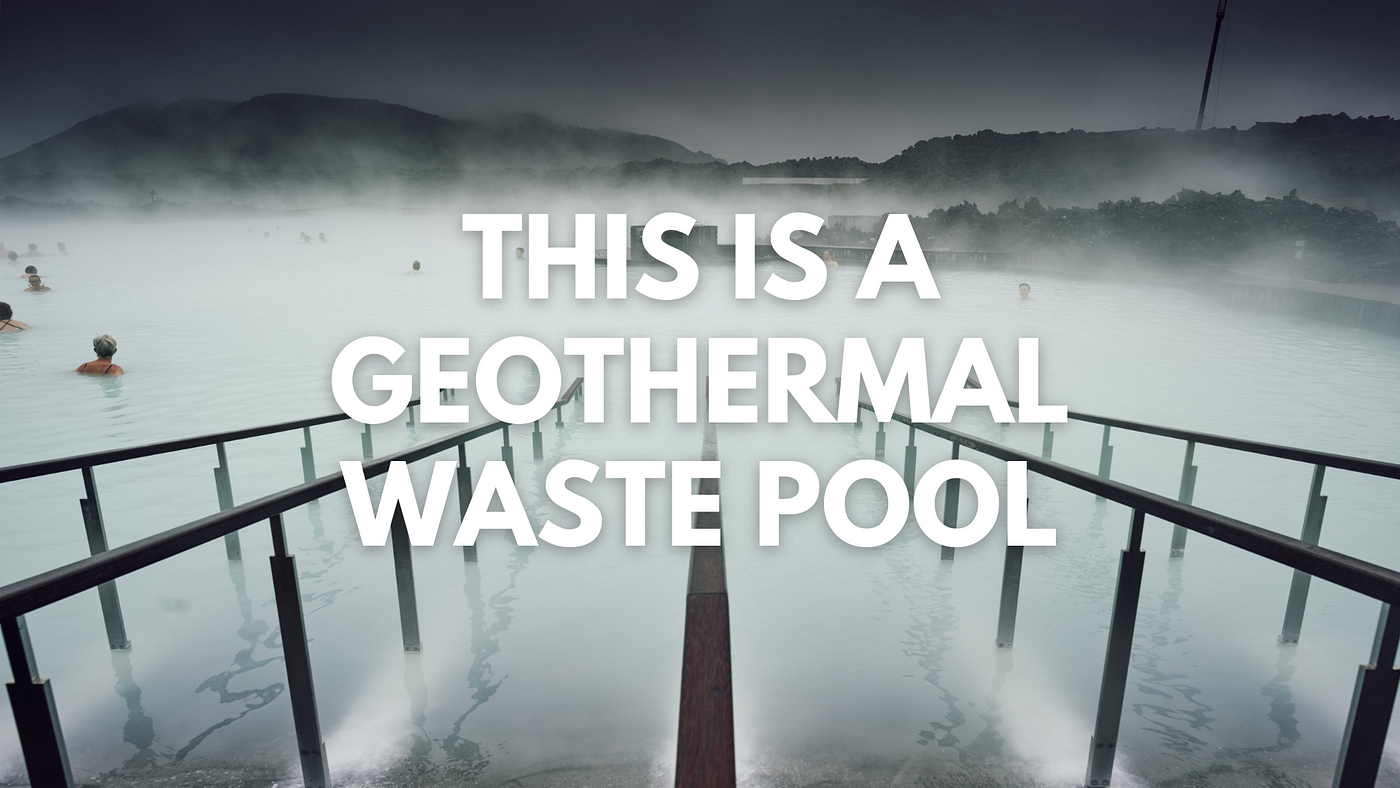

While some areas of nuclear plants will always be out-of-bounds, that doesn’t mean they can’t have a welcoming, public-facing side to them. The Svartsengi Power Station in Iceland uses the heat in volcanic rocks to create steam and hot water. In 1976, it became the first geothermal plant in the world to provide both electric power and district heating.

The plant works well, but there’s one problem: it produces wastewater high in mineral content that can’t be recycled. The operators decided to create large ponds to store the water. The ponds are made from a semi-porous volcanic rock that allows the water to drain away. The minerals are left behind, filling up the ponds and requiring new ones to be dug periodically.

In 1981, a psoriasis patient bathed in the waste pools (after a long battle with the plant’s operators) and found the waters soothed their skin condition. The news got out of the water’s supposed ‘healing powers, and soon permanent bathing facilities were set up. Visitors today pay $64 to bathe in the water and rub silica-rich mud (from the geothermal waste) onto their bodies.

You might have heard of the place: Iceland’s world-famous ‘Blue Lagoon’.

[Note 1 — as an aside, some geothermal waste streams are actually radioactive].

By complete accident, the Svartsengi plant had stumbled across the best public outreach exercise they could ever hope for. No amount of “educating the public” about the benefits of geothermal power could even come close to the normalizing influence of the Blue Lagoon. Not only is it safe, but people are also literally queuing up and paying to bathe in its waste!

Blue Lagoon works because it fits our idea of Iceland — cold and stark yet crossed with fire and the rawness of nature. It doesn’t matter that the water comes from an industrial energy plant.

Blue Lagoon works because it fits our idea of Iceland — cold and stark yet crossed with fire and the rawness of nature.

I wonder if there’s an example here for the nuclear industry. What if nuclear plants weren’t just seen as anonymous industrial sites, but instead became places for public leisure and enjoyment? Could this help to normalize nuclear and build public trust?

Though not rich in silica like Svartsengi, nuclear plants do produce huge amounts of low-carbon hot water and steam, a lot of which go to waste. A large health spa with saunas, steam rooms, and heated pools must use a tremendous amount of energy. Why not create a low-carbon health spa using clean heat from a nuclear plant?

Just like Blue Lagoon fits with Icelandic culture and the landscape, any nuclear-powered spa shouldn’t look like it’s been dropped in from space, but instead should harmonize with local cultures and landscapes and use vernacular architectural styles. While it would provide public information, its focus would be primarily on a climate-friendly leisure space.

Take, for example, if the Wylfa plant I visited were to ever get a new plant. Why not make its public-facing side a sustainable, luxury spa themed on the mythical druids of Anglesey (ancient priests said to have channeled elemental energies) and inspired by the island’s dramatic coastline and rugged architecture?

Or how about providing clean heat for huge tropical greenhouses, and partnering up with a local botanical school or research institute? What better way to show how low-carbon nuclear enables a broader ecosystem of clean technologies, as well as creates a novel income stream. It turns out the founder of the Eden Project in Cornwall, UK, is himself pro-nuclear [2]—I’d love to see a nuclear-powered Eden 2.0.

It doesn’t matter what it is — the goal here is to create a welcoming, attractive public space that generates positive associations for the nuclear project and builds trust with the public. Just like swimming in the Blue Lagoon was great for geothermal acceptance, having a tangible, on-site piece of public infrastructure that wouldn’t exist without the plant would win hearts and minds for nuclear.

New possibilities

In some countries, there are constraints on population density around traditional light water reactors due to fears of radiation during a meltdown. Many advanced reactors will eliminate (or else massively reduce the likelihood and severity of) this risk by design. This makes it easier for advanced reactor developers to include public spaces.

Oklo is leading the way with their Aurora fission powerhouse. To an outsider, Aurora appears to have been designed primarily for the public, with a welcoming staircase bringing you into a “community space” (the reactor itself will be locked away underground). This unique design should make local communities feel they belong in the space, rather than it being a fenced-off nuclear temple shrouded in mystery.

There are other bright spots, too. Ultra Safe Nuclear have plans for one of their MMR plants at the heart of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign campus.

Change is never easy

No doubt some within the industry enjoy nuclear secrecy, feeling like the high priests of a mysterious cult. Mostly though, it comes down to people sticking to what they know. The first step is accepting that maximalist security does come at the cost of negative public perception.

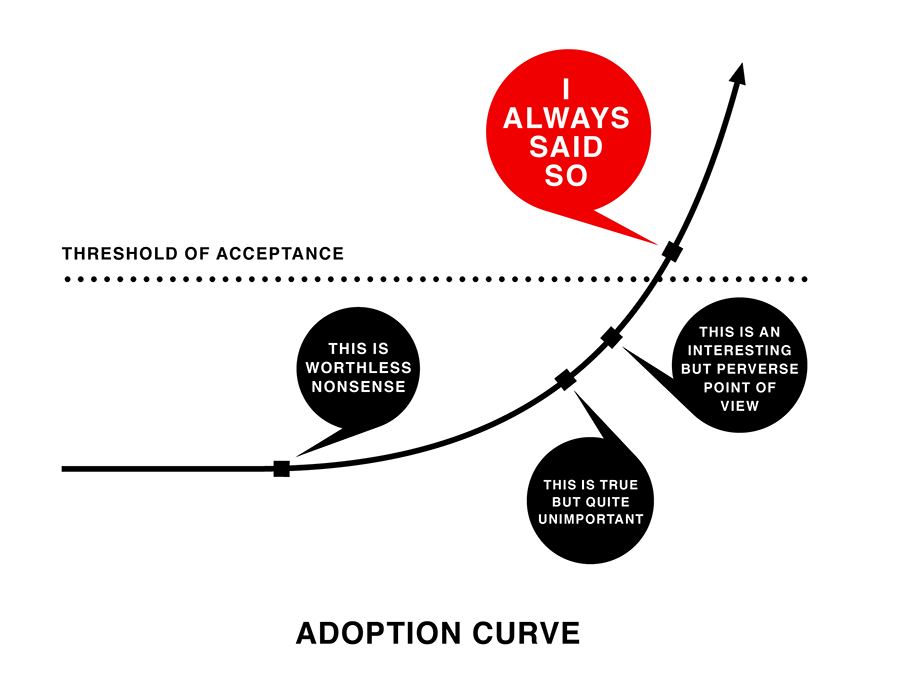

Culture cannot be changed overnight, but it starts with leaders in the industry championing a different way of doing things. Right now, that carries a risk of looking weird or idealistic but, as I’m always saying, good ideas have a way of bursting through the threshold of acceptance when you least expect it.

The industry is trying to get better at communicating why nuclear plants are good for their local areas. For example, the IAEA just released a new report on stakeholder engagement with tips to help developers through the long slog of consultation and communication needed to attain public acceptance.

While this kind of science-based engagement is essential, the industry shouldn’t be afraid to try something more “outside of the box”. To do that, the nuclear engineers will have to take a step back and let the architects and brand experts take the reins for once. After all, if you start with a project that people like and can connect with in their everyday life, it becomes less about public acceptance and more about public enthusiasm.

Afterword on district heating

District heating means providing hot water and heating to urban areas using a centralised plant. Several countries in the world have nuclear-powered district heating systems, including a huge new project in China. Nuclear district heat is the raw energy of the reactor connected to your home, separated only by a chain of heat exchangers.

It takes the community engagement model and flips it on its head; instead of bringing the public to the plant, we bring the plant to the public. I believe nuclear heat has greater potential to normalise the technology than nuclear electricity. There’s something special about the way a cosy radiator warms your bones on a chill, winter’s day.

Notes

[1] Radioactive minerals were found around geothermal wells at another geothermal plant close by to Svartsengi. Scientists then checked Svartsengi and declared it safe. Also, note that the United Nations agency responsible for reporting on ionizing radiation, UNSCEAR, found that geothermal energy leads to the highest dose of radiation per unit of electricity generated of any energy form. This is because forcing water deep into the volcanically active zones can bring to the surface significant concentrations of uranium and its decay products.

[2] Thanks to Henry Preston for pointing me to this article where Sir Tim Smit gives the impression he’s pro-nuke. You can also read more from Sir Tim on nuclear here.