Most experts agree that there are between 9 and 20 million tons of land-based uranium in the world, most of which hasn’t been discovered yet. At current consumption rates, this would provide a supply that lasts up to 230 years.

But that, of course, is only if we actually make moves to obtain it.

Uranium can be found underground in many countries, as well as in seawater, but around

two-thirds of the world’s current supply comes from Australia, Kazakhstan, and Canada. The U.S. has vast reserves of uranium that are largely untapped – especially in New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Texas, and Virginia.

There are a few different ways to mine for uranium. The traditional method is called opencast, or open-pit mining, where a hole is dug outwards from the surface of a mineral deposit to excavate a deep pit. Generally speaking, we get 1–4 pounds of uranium for every ton of ore. Another method is underground mining, which requires tunnels to be dug beneath the surface of the ground. In this method, the ore is obtained almost exclusively with machines. Underground mining is great for when uranium reserves are deeper in the earth’s crust, and it usually means less waste rock and environmental exposure as well. A relatively newer method is called insitu mining, where a solution is pumped into uranium-rich rock, and then when sucked back out, contains a slurry of uranium. While insitu mining is generally considered less invasive, the best mining method is unique to each site.

And I know what some people are thinking. Don’t uranium mines give people cancer and pollute groundwater? Well, in the past, some of them did.

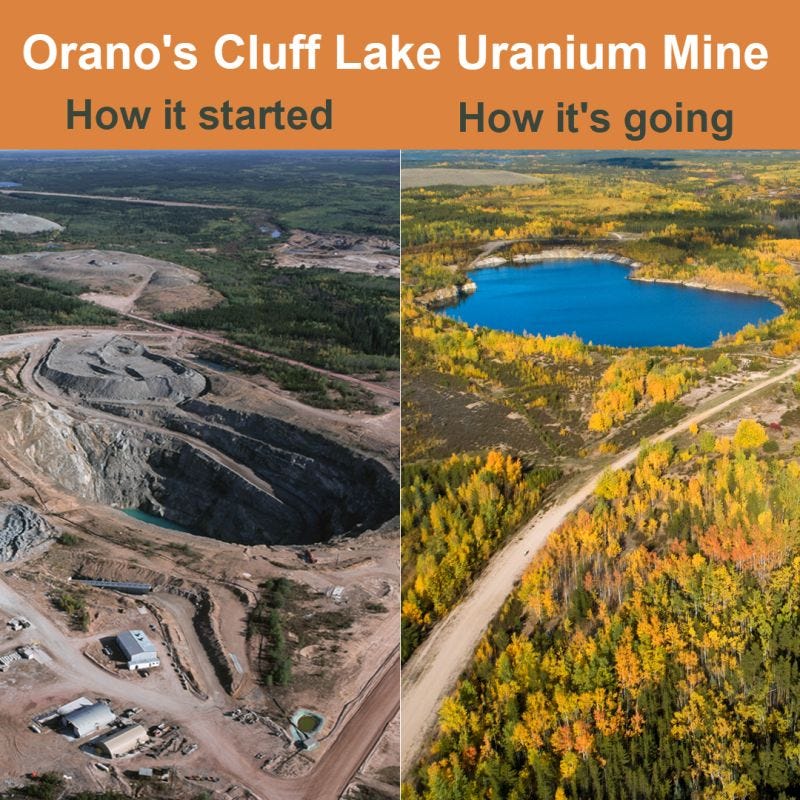

This was largely between the 1940s and 70s, at a time when homes were built with asbestos and lead paint and cars didn’t have seatbelts, while kids played with mercury in school and started smoking cigarettes at age 10. There was generally little safety precaution in this era, and things have changed a lot. Back then, when the uranium resources had been exhausted, mining corporations just packed up and left, leaving behind a mess and a public health crisis. Today the focus is on securing a plan to rehabilitate the site back to normal once the mine is closed, and storing away the financial resources to do so.

The closure and remediation phases of a mine’s life cycle are the parts that usually cause negative socio-economic and environmental impacts for nearby communities – not the actual mining part. While the focus should be on ensuring post closure safety for humans and the environment, past efforts favored short-term technical fixes over longer-term considerations.

These historical mines that operated on Indigenous territories have strategically excluded Indigenous voices from planning and decision-making. This is unacceptable, especially considering that many native populations have nuanced and spiritual connections to land. This research employed a qualitative document analysis of ten mine closure plans for active mines in Northern Canada to understand how the industry plans for closure of the sites, and whether or not mine companies are incorporating Indigenous knowledge into their remediation plans. What they found is that mine closure plans across Northern Canada inconsistently apply Indigenous expertise, priotizing technical aspects of mine closure over the social, cultural, economic, and ecological factors. For mine closures to be successful, they need to value community input and consider a wider scope of impacts. Mindful closure practices are currently being developed by national lawmakers, as well as mining corporations themselves. Improved closure plans in the uranium mining industry are revolutionizing the ability to reclaim land, restore ecosystems, and mitigate long-term environmental impacts.

Restoration of Orano’s Cuff Lake Uranium Mine in Saskatchewan, Canada.

The U.S, Australia and Canada have vast untapped reserves, and are uniquely positioned to meet soaring demand through extraction efforts that generate jobs, safeguard the environment, and establish these nations as clear leaders in the fight against climate change. Not only do these countries have vast uranium stores, but they’re also committed to strong regulatory frameworks, meaning that mines will be managed sustainably and responsibly. As the need for clean energy accelerates, ethically tapping into the uranium riches within our borders will become a moral and economic imperative.