How National Climate Plans Lost Touch with Reality

Author: The Kernel, Gayatri Karnik and Eric G. Meyer

In 2015, world leaders created the Paris Agreement to coordinate global climate action, requiring nations to submit detailed climate strategies to the United Nations. These take two forms: Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), updated every five years to outline medium-term goals, and Long-term Low Emission Development Strategies (LTS), which chart the path to carbon neutrality.

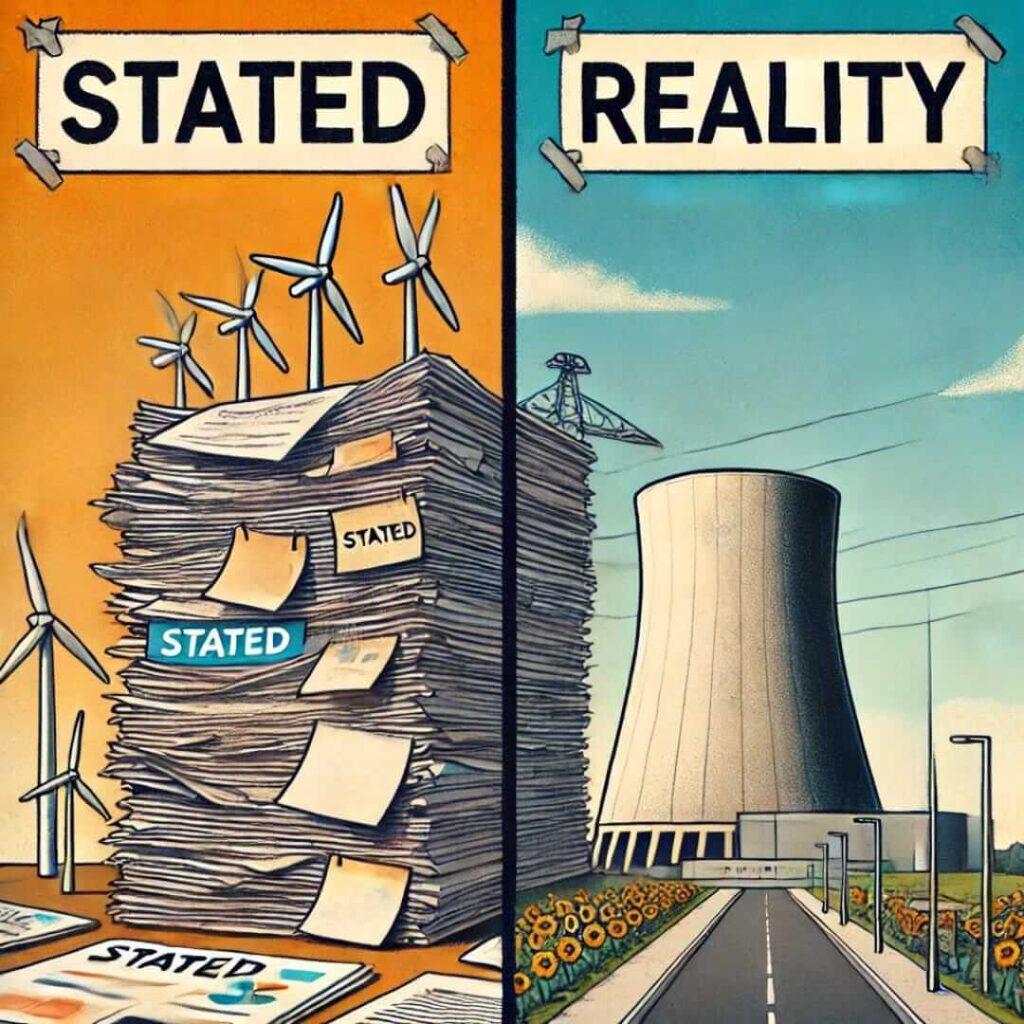

Today, there’s a striking disparity between what nations say in these documents and what they do. The gap is particularly glaring in the nuclear energy sector, where official climate commitments have failed to keep pace with rapidly evolving policy and energy realities.

The Great Nuclear Pivot

The 2023 global stocktake at COP28 marked a historic shift, formally recognizing nuclear energy as a decarbonization tool for the first time. During the conference, twenty-five nations made a landmark commitment to triple nuclear energy capacity by 2050. This dramatic evolution in nuclear policy stands in stark contrast to most countries’ official climate plans, which were written in an era of greater nuclear skepticism.

This seismic shift in energy policy is barely reflected in these nations’ NDCs and LTS documents—creating a credibility gap that threatens to undermine the very framework designed to coordinate global climate action. The timing is particularly critical: the next round of NDC submissions is due in 2025, offering a crucial opportunity to align official commitments with current nuclear ambitions.

The Paper Trail Goes Cold

The disconnect is particularly glaring among Triple Nuclear Pledge signatories:

- France: Long-Term Strategy, submitted in 2020, still targets a reduction of nuclear power down to 50% by 2035—a policy that has since been completely reversed with plans for massive nuclear expansion of up to 14 new reactors.

- The Netherlands: Once committed to a nuclear phase-out in its climate documents, now plans to build two new reactors, acknowledging that excluding nuclear energy would make its 95% emission reduction target virtually impossible.

- Japan: NDC maintains cautious post-Fukushima language about nuclear power, while the country actively works to restore nuclear to 20-22% of its electricity mix by 2030. It has already taken concrete steps, recently restarting the Onagawa Nuclear Plant.

- The United States: NDC primarily discusses “leveraging existing nuclear facilities” while remaining conspicuously silent on new construction. This understated language belies a dramatic reemergence of nuclear in recent years.

- South Korea: NDC makes no mention of nuclear power whatsoever, despite the country’s proven success in exporting its APR1400 technology to the UAE and a dramatic reversal of its phase-out policy to instead maintain nuclear’s 30% share of electricity generation.

- Sweden: Has abandoned its “100% renewable” target in favor of “fossil-free” electricity to accommodate nuclear expansion. Still, its LTS tiptoes around nuclear energy’s future role.

Eastern Europe’s Nuclear Commitment

Among Triple Nuclear Pledge signatories, Eastern European nations show particularly stark contrasts between ambition and documentation:

- Czech Republic: Climate documents barely hint at the country’s plans to significantly increase its nuclear production beyond the current one-third share of electricity generation.

- Hungary: LTS acknowledges nuclear power as necessary for climate neutrality but downplays its ambitious expansion plans, including new reactors currently under construction.

- Slovakia: Mentions new reactors only in passing within its strategy documents, despite broad public and political support for nuclear expansion.

- Slovenia: Shares a reactor with Croatia that meets nearly a quarter of its energy needs, yet its climate strategy only vaguely references plans for 2400 megawatts of new nuclear capacity.

- Ukraine: Maintains nuclear power as central to its energy security and plans four new reactors at Khmelnytskyi, yet its climate documents need updating.

Major Nuclear Powers Outside the Pledge

- China: Plans to build 150 new reactors before 2040, yet its NDC merely mentions nuclear power.

- India: NDC mentions plans for 63 GW of installed capacity by 2032 but frames it as an afterthought.

- Russia: Emphasizes nuclear technology exports while understating domestic expansion plans.

Time for an Update

The next round of NDC submissions, due in 2025, offers a crucial opportunity to bridge this credibility gap. Countries need to align their official climate commitments with their actual nuclear policies to maintain the integrity of international climate frameworks.

Looking Ahead

Nuclear power has emerged as a crucial tool in many nations’ arsenals. The disparity between official climate plans and actual nuclear policies must be addressed to achieve global climate goals.

Note: The full list of signatories to the Triple Nuclear Pledge includes The United States, Canada, Finland, France, Ghana, Jamaica, Japan, Republic of Korea, Mongolia, Netherlands, Sweden, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, Armenia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Moldova, Morocco, Poland, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, and Ukraine.

For an expanded overview and analysis of the existing NDCs and LTS for the twenty-six countries that mention nuclear in some way, click here.