Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline is happening. What does that mean for the climate and for geopolitics?

Written by Generation Atomic

January 6, 2020

by Håkan Lane and David Watson

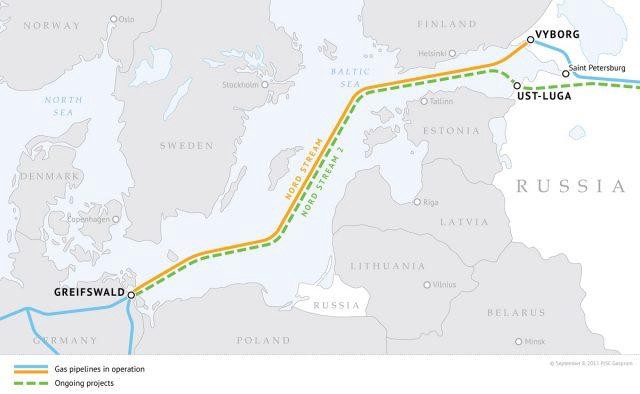

Nord Stream 2 is a planned, high-capacity sea-bed pipe that will pump gas from Russia to Germany, meeting that country’s increasing demand for the fuel for electricity and heating. Denmark’s recent planning approval for this new megaproject sends a confused message from a supposed leader in sustainable development.

The expansion will deliver gigawatts of power to European households, enough to power a country like the UK most of the time.

While natural gas is better than the disastrous coal plants currently in use in Germany, it is by no means a clean source of energy. Nord Stream 2 will lead to additional annual emissions of 106 million tonnes of CO2, equivalent to the emissions of the entire country of the Czech Republic.

Moreover, much of the gas comes from operations in Russian Arctic ecosystems, where many environmental organisations fear new oil and gas drilling threatens fragile ecosystems.

Nord Stream 2 also has enormous geopolitical implications. Current Russian gas pipelines pass through Ukraine and Poland. Some argue Nord Stream 2 thus deals a triple blow to Ukraine and Poland.

Firstly, it deprives those countries of valuable tax revenues. Secondly, if Russia turns off the gas to pipelines passing through Poland and Ukraine, this will have less impact on Western Europe than previously. And thirdly, it increases German dependence on Russian gas, thus making it less likely that the German government would intervene in favor of Poland or Ukraine if threatened by Russia. The owners of Nord Stream 2 refute these claims.

Others say Nord Stream 2 is simply a piece of realpolitik: Germany’s desire to simultaneously drop both coal and nuclear power (despite its low carbon credentials) while switching to variable renewables has left it scrambling for a source of firm power. With hydro not an option, methane gas was all that was left to Europe’s would-be climate leaders.

With German politicians recently trying to get methane gas included (and nuclear excluded) as a “green” form of energy within EU parliament declarations for COP25, the country really does seem to have backed itself into a very strange corner on climate policy.