A new approach to sustainable finance will help us build the future we need.

The year 2019 saw a dramatic shift in public awareness of the climate crisis. The science is clear; if we do not make rapid changes to how we use energy and consume resources, it is likely that we will face runaway global warming with potentially devastating effects.

What is not clear is how to address the problem. Technology alone is not sufficient; we need a cultural, political and economic shift away from current short-term thinking to a long-term, systems-based approach.

The world has seen remarkable changes over the last 100 years. The explosion of growth through technology has become a global race. This has transformed our society for the better, bringing health, prosperity and quality of life to billions of people.

Despite this, we now risk overshooting the limitations of our planet. Much like rabbits released onto an island devoid of predators, our growth and consumption has outstripped the natural rate of replenishment. For the rabbits to survive, they need predators to control their numbers to maintain a sustainable population size. In order for humans to survive, we need a system in place to maintain a sustainable consumption rate.

Climate Leadership

Due to the nature of the challenge, no country can solve it alone. Some argue that reducing emissions in the EU and UK is meaningless compared to the increase in emissions from countries like China and India. While it is true that the UK only contributes about 1% to global emissions, it still has a powerful voice and global influence.

London is the number one financial capital in the world. The investments held in the City of London account for 15% of global emissions. Transitioning the City of London to a green financial system would be game changing and is a huge opportunity for the UK to become a climate leader.

System-level thinking

For this transformation to succeed, we need to incentivise investments that deliver benefits at a system level. Building a sea wall to protect a village may cost £1 million, but prevents £10 million of property damage from future flooding. Overall there’s a net gain of £9 million.

As sea levels rise we will need to invest more in sea defences, as well as many other adaptation projects. But how do we monetise avoiding losses? How do we reward an investment whose value is dispersed, indirect and difficult to quantify?

Historically this kind of investment has been the role of public sector funding, but without mobilising private sector capital, we cannot hope to achieve the rate of change required to adapt to climate change.

To do this, we need to understand both the risks presented by climate change, and how well investments address these risks, so that we can fairly compare the value of each decision.

What not to do

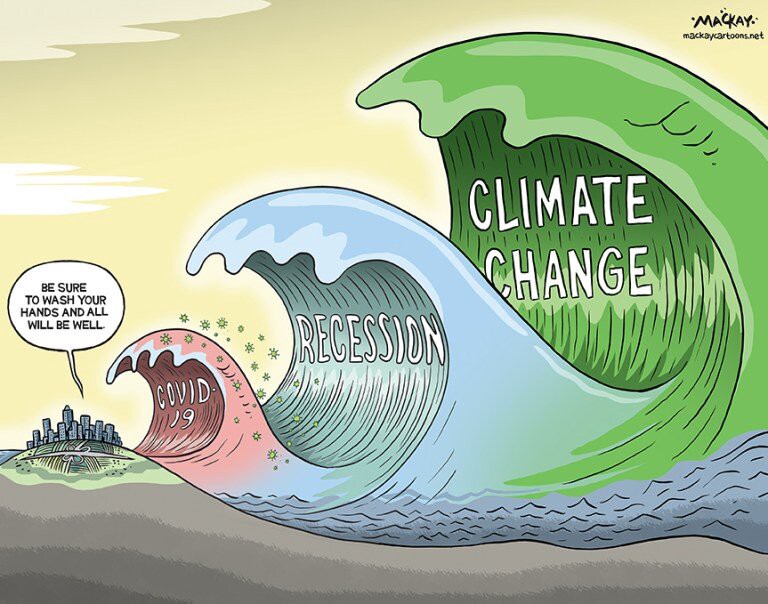

The Covid-19 crisis is a great example of what happens when risk is not properly assessed and mitigated against. According to the World Economic Forum, Covid-19 has cost the world economy $11 trillion, with another $10 trillion expected in future losses. By comparison, preparing for a pandemic would have cost around $39 billion a year — 500 years worth of preparation.

The impact of Covid has been abrupt and extensive. The impact of climate change will grow exponentially for centuries to come, but even in the next few decades the economic damage will be significant. Through direct effects such as droughts, flooding and crop failures, the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Climate Change Resilience Index estimates it will cost the world economy $7.9 trillion by 2050.

A framework is required in which accurate data is available on the risk presented by climate change. This will empower investors to make the right choice, and hopefully trigger the biggest realignment of capital in history.

Vision and mission statement from the UK Green Finance Institute.

Kick-starting the transformation

The UK recognises this and is working towards establishing these mechanisms. In October 2019, the first ever public sector green finance summit was held in London. Hosted by the UK government with support from the University of Oxford and the UK Green Finance Institute, the conference looked at how to transition to a green financial system. It drew leading figures from the financial world as well as representatives from 16 other countries.

The range of speakers was impressive and together they presented a vision for how finance can enable a green transition. Increasing transparency around risk was highlighted as a key driver to this, pointing towards the important work that the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) is doing around this topic.

The TCFD was first announced at the Paris climate negotiations in 2015. It helps investors understand their exposure to climate risks and helps companies disclose this information in a clear and consistent way.

The Bank of England is a prominent supporter of this process, having used the framework to disclose all their climate risks in this report from June 2020, the first central bank to do so. Mandatory financial disclosure is still some years away, but through leading by example the BoE aim to encourage others to do the same.

Beyond the financial world

Driving enough clean investment to tackle global emissions will require more than just climate risk financial disclosures. Each sector must create their own tools for establishing a taxonomy of what is ‘green’, what is ‘brown’, and move towards measuring the system costs, not component costs.

For example, in the electricity sector, generating costs are measured with a metric known as Levelised Cost Of Electricity (LCOE). It sums the total cost to build, operate and decommission a power-generating asset divided by the total energy output over its lifetime.

LCOE is used to compare costs of generation between different technologies, which is useful to an investor who wants to know which assets are most likely to provide them with the highest return. However, this does not account for the total system cost of integrating that technology into an electricity grid.

The LCOE of both wind and solar has dropped sharply over the last decade, but as the proportion of renewables in our grid increases, the cost of balancing supply and demand increases exponentially. Energy storage can go a long way to addressing this issue, however this added cost is not being included in the LCOE. This report explains in further detail the failings of this approach and why system-level analysis is key to building an optimal electricity grid.

Looking simply at LCOE, other low-carbon generation technologies like nuclear appear expensive compared to renewables. However, in Germany where renewables now make up 42% of electricity generation, carbon emissions from electricity are 8 times higher than in nuclear-powered France. Electricity in Germany also costs twice as much as in France.

LCOE is — on its own — not a perfect measure of real world costs.

If we want to live in a truly sustainable world, we need a systems-based approach. We also need effective financing to enable change today. The cost of delaying climate action could be catastrophic. But it is not too late if we act now. With ambitious leadership and a thriving green economy, we can build a better world for both ourselves and all future generations.